Inside Oakmont Country Club: America's Most Difficult (And Unique) Golf Course

Today's newsletter includes a few thousand words breaking down everything you need to know about Oakmont Country Club — the financials, redesign, maintenance, and dozens of other interesting facts.

If the U.S. Open is the toughest test in golf, there is no better place to play it than Oakmont Country Club. Located 10 miles outside of downtown Pittsburgh, the 122-year-old club will have the world’s best golfers second-guessing their game this week.

To conquer Oakmont, you must have complete control of every club in your bag. The average fairway is only 28 yards wide, requiring precision off the tee. If you miss a fairway, you’ll end up in 5-inch-thick, wrist-breaking rough or one of the course’s 168 bunkers. That’s an average of nine bunkers per hole, not to mention the infamous “Church Pews” bunker that stretches over 100 yards in length and 40+ yards wide.

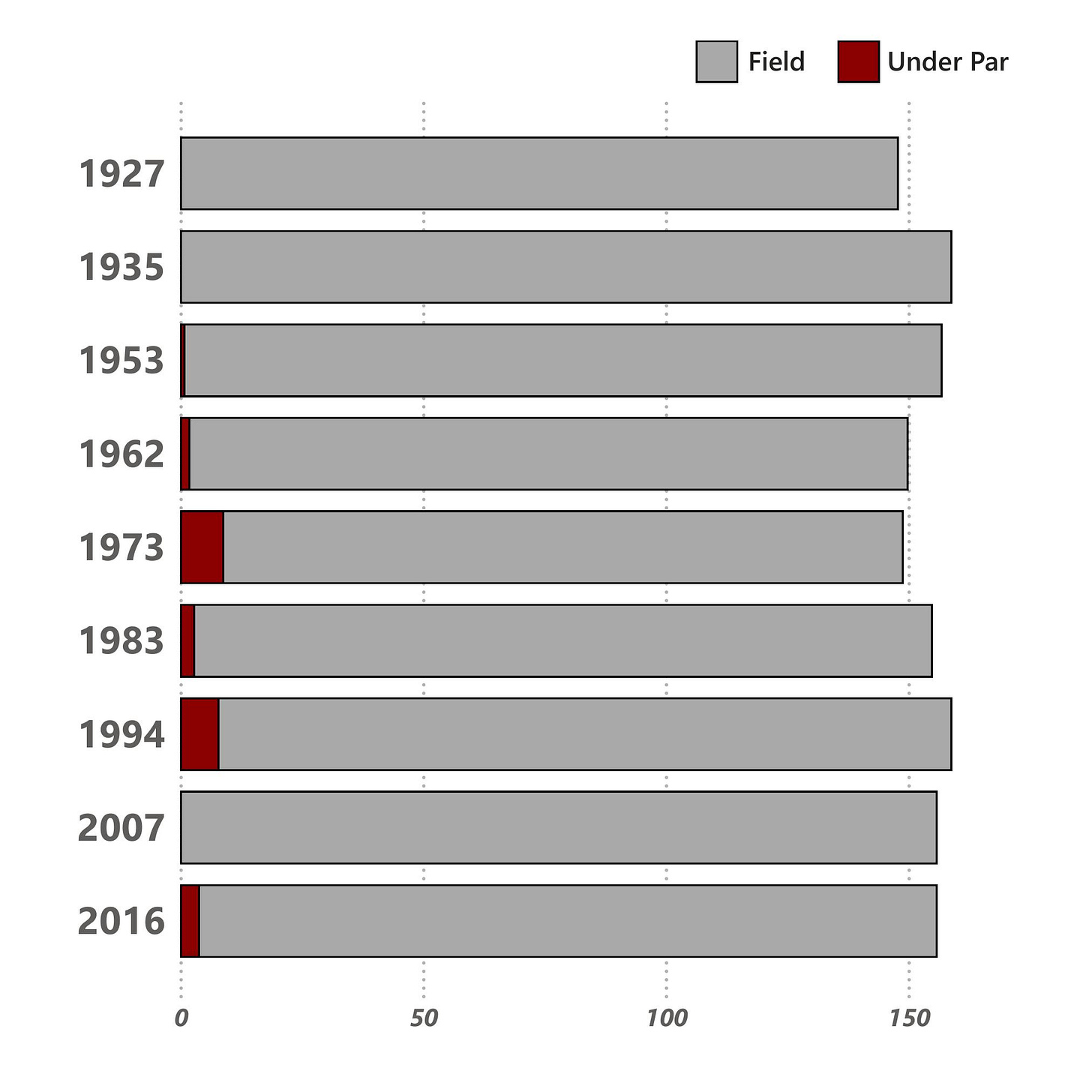

Even if you drive the ball well and feel good with your irons, everything can fall apart when putting. Some greens are massive, while others are small. If one is wide, the next is narrow. Oakmont’s greens are so firm and fast that they literally led to the invention of the Stimpmeter, the device golf courses use to measure green speed. In the last nine U.S. Opens held at Oakmont Country Club, only 27 out of 1,385 players have finished under par — that’s less than 2% of all U.S. Open participants (over nearly 100 years).

“You can hit 72 greens in regulation in the Open at Oakmont and not come close to winning,” Arnold Palmer famously said.

Oakmont’s challenging layout is only part of what makes the course so interesting though. As players walked into the clubhouse this week, they could feel the club’s history and tradition. Wood-paneled walls are lined with memorabilia from the 1900s. Each locker still has the secret compartment that members used to store alcohol during Prohibition. There are working phone booths in the locker room, but no air conditioning. And when players sit on the wooden benches to put on their shoes, they can literally see old metal spike marks and scuffs from the likes of Bobby Jones, Walter Hagen, Ben Hogan, Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Tiger Woods, and others.

Oakmont is so old that the government used eminent domain to construct a highway through the middle of the course in the late 1940s. Due to the course’s elevation, the Pennsylvania Turnpike’s 2.5 million weekly travelers wouldn’t even know the course is right next to them (outside of a few banners on a chain link fence twenty feet above them). But players and fans still have to cross the bridge to reach holes 2 through 8.

The USGA even threatened to remove Oakmont from tournament consideration due to a logjam on the bridge during the 1994 U.S. Open. But then hedge fund billionaire (and Oakmont Country Club member) Stanley Druckenmiller financed the construction of a second bridge for approximately $750,000, and all was forgiven.

However, that doesn’t include the $75,000 fee that the Turnpike Authority charged the club to close down the highway for 20 minutes to perform one part of the construction.

Oakmont is such a fascinating venue because it has withstood the test of time. While other championship courses are buying up land to deal with the increased length of the modern game, Oakmont’s layout looks nearly identical to what it did 100 years ago.

To understand how that's possible, you first need to understand Oakmont’s history.

In 1903, a man named Henry Fownes purchased 191 acres of farmland just 10 miles outside downtown Pittsburgh for $78,500. The land was barren with train tracks running down the middle, but Fownes didn’t care. It was perfect for what he needed.

Fownes had recently become wealthy after selling his iron and steel business to Andrew Carnegie, the richest man in the world at the time. But when a doctor misdiagnosed him with a terminal illness, Fownes thought he only had a couple of years to live and decided to enjoy life. Fownes traveled to Scotland to play some of the world’s best golf courses, and when he returned to the U.S., the 47-year-old made it his mission to build an unrelenting links-style course in the hills of Pittsburgh.